When liquids behave like solids

But now in a new study, physicists have shown that a droplet of liquid mercury can undergo a reversible compression process like a solid object does, as long as the surface it interacts with is "super-mercury-phobic." Such a surface is very resistant to mercury, so the mercury droplet does not spread out like a typical liquid droplet does.

The physicists, Juan V. Escobar and Rolando Castillo at the National Autonomous University of Mexico in Mexico City, have published a paper on how a liquid can behave like a solid in a recent issue of Physical Review Letters.

"On one hand, we have developed a novel technique with huge potential to study wetting in general and in particular the force of adhesion between a liquid and a solid, and on the other hand we helped bridge two apparently separate areas of physics (surface physics and mechanics)," Escobar told Phys.org. "From a more fundamental point of view, it could be said that our results show how Nature does not care about the specific source of the restoring force in a process of compression: as long as it enters the energy equation in mathematically similar form, the phenomenology will be the same.

Normally, the compression of a liquid droplet onto a solid surface is a hysteretic process, meaning that the droplet's contact angle depends on its compression history. However, previous studies have predicted that the contact angle hysteresis can disappear under certain conditions, essentially making the compression process reversible.

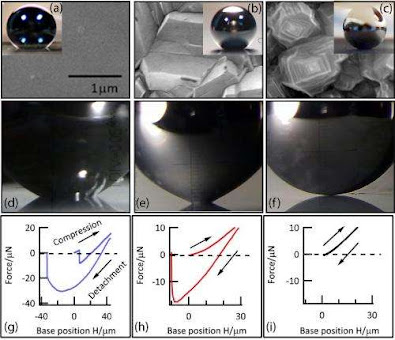

Here, the physicists experimentally confirmed this prediction by compressing mercury droplets onto different types of surfaces. On rough surfaces, the droplets still exhibit contact angle hysteresis, but the droplets on the super-mercury-phobic surface do not. The researchers attribute the vanishing contact angle hysteresis to an extremely low surface energy between the droplet and the surface.

Along with this finding, the researchers made an unexpected discovery: even though the mercury droplet's contact angle hysteresis has vanished, it still has a small but measurable adhesion force, which is also independent of its compression history.

Taken together, these two observations mean that the mercury droplet behaves like an elastic solid during a repeated compression-decompression process. The researchers explain that this behavior occurs because the dewetting of a liquid can be thought of as the equivalent of the detaching of an elastic solid. These results agree with a theoretical model in which the surface tension of a liquid is the counterpart of the restoring force of an elastic solid. The experiments could have applications for further investigation of a variety of liquid behavior.

"Our instrument can be used to study the dynamic wetting of a wide variety of liquids and surfaces," Escobar said. "In particular, it can be used to study the dynamic formation of the so called 'pinning points' that make the contact line stuck (or pin) on the surface (this study is underway). It can also be used to study the phenomenon called non-plastic ageing (this study is also underway). Also, our instrument could be used with polymers as well."

#ShearThickening#Dilatancy#SolidLiquidTransition#Pseudosolid #FluidMechanics#NonNewtonianFluids#Rheology#Quicksand #Oobleck#BodyArmorMaterials#Suspensions

Comments

Post a Comment